The following is the second in a series of blogs. To read Part I, go HERE.

The following is the second in a series of blogs. To read Part I, go HERE.

In November 2012, I was on the beach packing up to leave after a surf, when my friend Crystal happened by. We chatted briefly, and then, out of the blue, she invited me to participate in a temazcal. A temazcal is a ceremony that takes place in a small enclosed space with a hole dug in the ground at the center into which burning hot stones are placed. Water is poured over the white hot stones to create lung-searing steam, which causes sweat to pour from every pore in your body such that you are transformed into something resembling a fountain. It purifies your body and, purportedly, your spirit. I imagine if you’re impure enough, you might vaporize entirely, leaving behind just a shell of skin in a pile on the dirt floor.

I’d participated in a temazcal with Crystal a couple of years prior and found the intense heat overwhelming, the result more exhausting than invigorating. I’d barely managed to remain in the little enclosure and, desperate to get some cool air into my lungs, had to lie with the side of my face in the dirt near a flap of the tarp covering the lodge’s frame. This time though I was three days into a juice cleanse and thought her invitation rather serendipitous. All that sweating would help me take the cleanse to another level, if I could only withstand the claustrophobia and intense heat.

As I ruminated over whether to accept her invitation, Crystal continued, “If you decide to come be sure to bring a blanket and warm clothing…oh and a candle.”

I looked at her curiously, not understanding.

“The Huichol may be coming too,” she said, almost as an after thought.

“Padre! (cool!)” I exclaimed.

With her mention of the Huichol the decision was made easily and If it weren’t for the fact that my meaning would be totally lost in translation, I would have said, “I’ll be there with bells on.”

The day of the temazcal three skinny dogs announced my arrival as I pulled up to Crystal’s boyfriend’s house on my ATV. Fernando’s property sits perched on a hill overlooking the Sea of Cortez and as the sun set behind the ochre hills, the sky and its reflection in the glassy sea slowly turned shades of soft pink and lavender. Crystal emerged from one of several small buildings on the property to call the dogs off. The atmosphere was positive and inviting. We embraced in greeting and chatted briefly when a car pulled up the driveway. Four people emerged – two men dressed in the characteristic garb of the Huichol, a third man and a woman, both dressed in modern western clothing. Like the man from the gallery years ago, the Huichol wore loose white cotton shirts and pants with brightly colored embroidery around the bottom, across the chest and around the wrists. On their feet they wore huaraches woven from narrow strips of leather. The younger Huichol had a rectangular, red bag embroidered with deep purple flowers slung diagonally across his shoulder. He would keep the bag slung there throughout our time together – only later would I learn its significance.

The day of the temazcal three skinny dogs announced my arrival as I pulled up to Crystal’s boyfriend’s house on my ATV. Fernando’s property sits perched on a hill overlooking the Sea of Cortez and as the sun set behind the ochre hills, the sky and its reflection in the glassy sea slowly turned shades of soft pink and lavender. Crystal emerged from one of several small buildings on the property to call the dogs off. The atmosphere was positive and inviting. We embraced in greeting and chatted briefly when a car pulled up the driveway. Four people emerged – two men dressed in the characteristic garb of the Huichol, a third man and a woman, both dressed in modern western clothing. Like the man from the gallery years ago, the Huichol wore loose white cotton shirts and pants with brightly colored embroidery around the bottom, across the chest and around the wrists. On their feet they wore huaraches woven from narrow strips of leather. The younger Huichol had a rectangular, red bag embroidered with deep purple flowers slung diagonally across his shoulder. He would keep the bag slung there throughout our time together – only later would I learn its significance.

We made our introductions and I hugged each of them in turn. The shaman, Guadalupe, hugged me stiffly and kept his left hand clenched at his heart. To guard it, I thought and wondered if perhaps hugging a shaman was inappropriate. I turned to the woman named Mio and we chatted while the others got organized. She was attractive with fair skin and brown eyes. I noticed immediately a gentle, loving energy about her. The man, Ajax, with whom she’d come was of small stature with a short, manicured black beard. He quickly disappeared after we’d been introduced, helping with the preparations. I was surprised to learn I was the only foreigner taking part.

As the sky began to darken, we built a pyre of wood and stones from a large pile of driftwood Fernando and Crystal’s sons, Mauricio and Tonatui, had gathered earlier that day. The stones, about the size of a large grapefruit or pomelo were full of small round holes like lava. As we worked, Guadalupe began chanting a blessing over the wood and stones. When the pyre was several feet high and the stones, twelve in total, were carefully nestled within, Fernando lit the fire. We all took several steps back as it grew and the heat intensified.

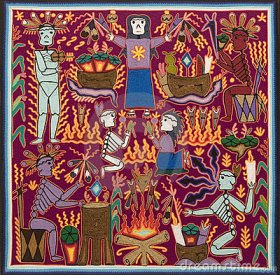

Mario, Guadalupe’s assistant, laid out a small altar, low to the ground between the fire and the white plastic chairs he and Guadalupe would sit on throughout the ceremony. The altar consisted of a burgundy cloth laid over a platform only a few inches high onto which sacred objects were placed. Guadalupe prayed over them in a low rhythmic chant. I could not understand the words as he spoke in Wixárika (pronounced wee-rá-reeka), the Huichol language. He held a stick with large feathers tied to it, waving it up and down, back and forth, gesturing to the four compass headings as he prayed quietly. Crystal had instructed me to bring two candles and ribbon with me. I placed these on the altar alongside the others with a small box of sandalwood incense. According to Huichol mythology, candles represent the illumination of the human spirit and hold the sacred gift of fire from the sun and fire gods. Along with the ribbon tied around it, the candle served as my offering and payment to the deities for the opportunity to be there that night. Both the candle and ribbon I’d brought were green, which symbolize the Earth, Heaven, healing, the heart, and growth in Huichol mythology.

It seemed understood that Guadalupe shouldn’t be disturbed as he went about his incantations and Crystal’s older son, Mauricio, asked his assistant Mario about something on the alter.

I listened as Mario gestured at several small, round, grayish green cactus buds and explained, “Before eating, first you must remove the small hairs from the skin of Hikuri. This is where some of the bitterness comes from. Then chew it well before swallowing.”

He turned to me and gnashed his teeth together to demonstrate, not realizing I understood Spanish.

“We will eat the cactus?” I inquired of Mario.

“We will eat the cactus?” I inquired of Mario.

“Yes, if you want to,” he confirmed.

I looked at the pile of small buds Mario had removed from the red bag he carried over his shoulder and placed on the altar. Peyote! I felt my pulse quicken. This was completely unexpected. Should I eat it? Was I in the right frame of mind and spirit? But what an opportunity to eat peyote under the supervision of a Huichol shaman!

Looking for clarity, I asked Crystal and she explained that yes, we could eat the peyote if we chose to. No one was required to do anything they did not want to. She explained now why she’d asked us all to bring blankets and dress warmly.

“We will stay up all night, if we can, and watch the fire. It is part of the ceremony. Guadalupe and Mario will stay until after sunrise.”

All night?! I felt my excitement mount along with a hint of trepidation. Where would this adventure lead?

Here is the link to Part III of Mystic in Mexico.